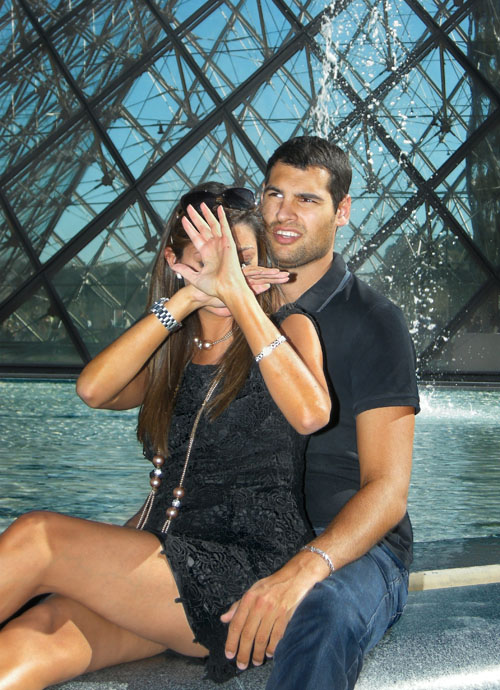

David Henry with Pierre Pradeau, a Parisian who never minded having his picture taken. —photo by Céline Vielcanet.

A classic example of how difficult candid photography can be in Paris and France: A young woman flipping out because I’m taking a photo of her while someone else is taking portraits.

I photograph people interacting or in conflict. I find my subjects in public places: fairs, rush hour crowds, subways, and parks. My ideal photo frames an action, a moment of decision being played out on a stage. They capture the element that makes the most ordinary of moments suddenly look unusual, somewhat transcendental, but still pleasant to look at. I am always looking for irony, both dramatic and visual.

In the early 1980s I started taking more and more photographs of homeless people. For me, the daily lives of these people are emblematic of the shift in political and social morals that occurred in the United States at the beginning of the 1980s and continues today. My photographs are a form of biography, telling stories about these and other people’s lives. Viewers’ reactions vary widely—shock, denial, revulsion, morbid curiosity, amusement.

In any case, my pictures ask the viewer to recognize and acknowledge people they would have otherwise ignored. I moved to Paris in September 1996, a move that has quite naturally changed the way I take photographs.

What is it like for an American photographer working in Paris?

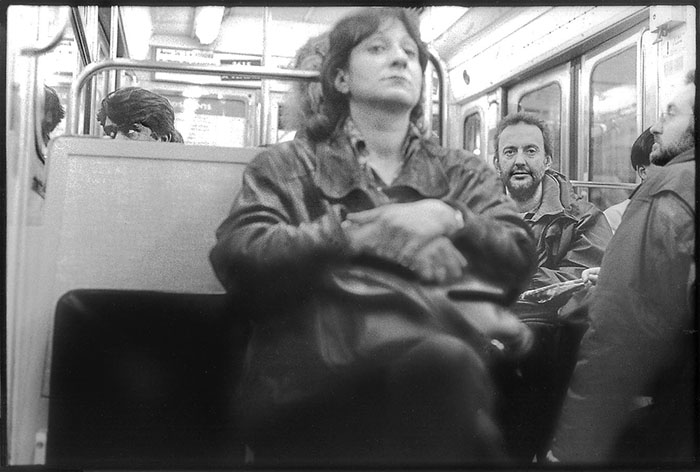

Some people on the Métro, two if not three of them are staring glumly and impassively in to the lens of my camera which I was holding in my lap.

When there is a scene I would like to photograph without disturbing the action, I keep the camera at waist-level and don’t use the viewfinder. If the scene is especially delicate, I don’t look at my subject, or even turn toward them. In this mode, photography becomes a visceral activity. My hands and forearms, connecting the camera to the rest of my body, become the viewfinder, another sort of peripheral vision another “eyes.” The photographs that come out of this work have a spontaneous feel, a physicality. They are taken, literally, at “gut level” and reflect that to the viewer.

I have been taking pictures in this manner (when the occasion requires it) since the early 1980s. I have become used to switching into this mode when putting a camera in front of my face would ruin a picture and I’ve become used to obtaining my desired results. While visiting Paris for ten days in the spring of 1996, I used my habitual techniques for taking candid pictures. After returning home to Boston, Massachusetts, I printed my pictures and found that almost all of the subjects I had intended to take candids of were, in fact, aware they were being photographed.

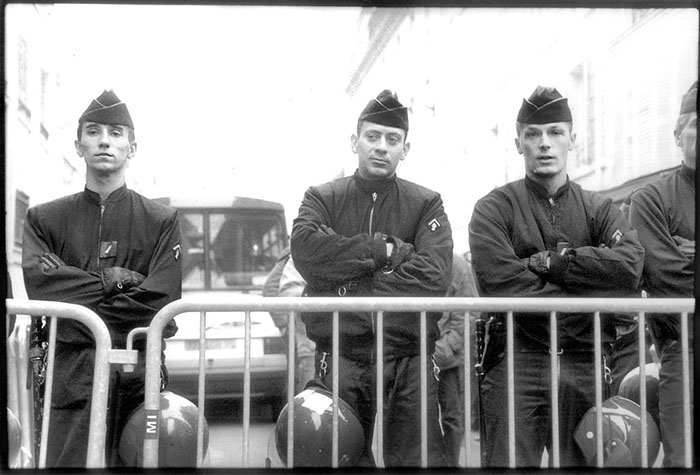

A group of CRS (Compagnie Républicain de Sécurité) in front of some Jussieu University students protesting against asbestos contamination in their school buildings.

In these pictures people are gazing calmly, directly into the lens. Unused to this sort of result, I was disappointed at first. But when I showed this collection of pictures later on, people found something intriguing and even startling about the frankness of the subjects.

This experience piqued my curiosity about why Parisians are so much more aware of the camera, relative to the Americans I have photographed. Could this difference be due to the pervasive influence of television in American culture and the passive nature of “looking” that television teaches? I’m curious, too, about why Americans become fearful and self-conscious when they do notice they’re being photographed, while the Parisians I encountered were unafraid and unself-conscious as subjects.

Do Parisians see photography as a creative activity, while Americans perceive photography as a way of taking possession of something—a moment, an event, a face, a body? (After all, in English one’s picture is always “taken” while in French sometimes on se fait photographier.)