The Kodak X-15, a Christmas present in 1973, took 27-mm square pictures on 126 film.

The Kodak Pony II, my first 35-mm camera. I remember paying five dollars for this entry-level camera from the 1957 at a flea market in 1975. Because it had no light meter or rangefinder, I had to guess the exposure and distance.

The Sears Tower Reflex III, my first 2¼ inch square camera that I bought for eight dollars at the same flea market in 1976, with which I still had to guess the exposure and focus.

The Praktica LLC, my first 35-mm reflex I bought in 1977 for $100, included my first light meter and I no longer had to guess the distance.

The Nikon FM, my first Nikon I bought the moment I could afford its $200 price tag in 1981. The camera’s light meter was so easy to use I generally forgot that automatic exposure was not among its features.

The Hasselblad 500C, my second 2¼ inch square camera, purchased in 1984. The camera had no light meter so I either used my Nikon, or I guessed the exposure as I had before high school.

The Nikon F70, bought in 1999, my first camera that does automatic exposure, which learned to love very quickly. I was impressed to see how accurate Nikon’s through-the-lens flash metering is.

The Nikon Coolscan IV, my “first digital camera”, making 11-megapixel scans of slides and negatives, it quickly replaced my enlarger and darkroom equipment.

The Nikon F4, Nikon’s top of the line, cutting-edge professional offering from 1986–1996, a camera I bought in July 2006. A waist-level viewfinder can be used with this camera, reminding of the Hasselblad, fantastic for interiors and candid photography.

The Nikon Coolscan V, a dream of a film scanner, that makes 20-megapixel scans of my negatives and slides.

The Nikon D90. Finally taking the plunge, I bought my first digital reflex in December 2008.

The Nikon D600 I acquired in December 2012, with 24 megapixels, a full-frame sensor and fine image quality at high sensitivities, all of this in a body that’s much smaller and lighter than a F4, a D3 or a D4.

The Nikon D800 I bought in June 2024 for €300, fantastic deal considering that it sold for almost €3,000 new. Digital cameras have evolved so much after 2010 that the best deals are used cameras. The downside is that its body is about 10% bigger and heavier than the D600. It’s impressive and entertaining to see my equipment’s progression in technology and quality from the top to the bottom of this column.

My opinions of the Internet and the World Wide Web are strong and divergent. Many web sites are full of gratuitous special effects and advertising, though there’s not much preventing people from publishing good, creative work on the Web. My web site serves as a permanent exhibition space which I can update as my work evolves. The Web offers another kind of democratization for publishing, as the advent of desktop publishing in the late 1980s offered.

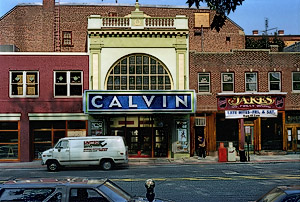

The passage of a tow truck improves a photo in Northampton: Hover over this picture to see the truck disappear; take a look at a bigger version of this example.

The phrase “computer-generated art” implies going beyond the possibilities of photography, drawing and painting and film; mixing images and media and generating images that are, in the realm of computers, “organic”, having never been touched by the human hand. While I admire these new possibilities, I take advantage of them rarely, only as an artistic diversion. I use computers to distribute my pictures in ways I couldn’t without computers and to enhance my photographs in ways I never could in a darkroom. You can take a look at a before and after example of how I rescued a picture by editing it with Adobe Photoshop.

The dawning of the digital era

Naturally, the “digital” in digital photography means computers. Until the early 1990s people would give you a funny look if you suggested that computers might have something to do with photography. In the 1980s computers didn’t interest me at all because they were at best digital typewriters.

When Adobe tells you something, it’s just “because”!

Like it or not, the main interface is and will be for a long time the keyboard. Luckily I learned to touch type on electric typewriters in high school and never forgot. The first computer I liked at all was the Mac Plus in 1989, because I saw that all kinds of neat things could be done on it, like word processing, graphic design and page layout, though working on pictures wasn’t possible because it had a strictly black and white screen, with no grey scale values.

Digital photography: scanning black and white prints

David Henry taking pictures of the fontaine «des Quatre Points Cardinaux» in front of Saint-Sulpice Church in Paris, September 18th 2006. —photo by Linda Schenck.

A couple of years later I was scanning my black and white prints with flatbed scanners and improving those scans in order to prepare them for printing in newsletters, magazines, books, etc. I vastly preferred removing dust and scratches with the mouse instead of the triple zero brush and Spotone™ inks and saw that I was indeed able to make moderate brightness and contrast adjustments region by region.

Digital photography: scanning color negatives and slides

In the mid-1990s I started to work in digital color, on scans of slides and negatives. At the time film scanners were too expensive, costing at least two or three thousand dollars and affordable computers weren’t up to the task of handling high-resolution color images. This changed after the millennium; I bought an iMac and a Nikon Coolscan IV film scanner in February 2001. A few months later I sold my enlarger and all my darkroom equipment because I wasn’t using it any more.

Using a scanner and image editing software, I was able to make better prints than I ever could with an enlarger in a darkroom. Furthermore, computer technologies allow me to make my own color prints, something I had hardly ever done in a darkroom because of the time, patience and expense required. And digital photography has to be gentler on the environment than printing in a darkroom.

The first “reasonable” digital reflex cameras came out in 2003, with six megapixels of resolution and costing two or three thousand dollars. I regarded them as toys because my Nikon film scanner did 11 megapixels and cost half as much. Digital cameras had a long way to go before they could match the cost, ease of use and transportability of 35-millimeter color film.

Digital photography was coming out of its adolescent phase in 2005, there were cameras offering 12 megapixels of resolution, previously unavailable at any price, but they were still two or three times as expensive as my scanner. Digital cameras back then didn’t give nearly the exposure latitude that color negative film provides. I was afraid of being disappointed in getting a twelve-megapixel camera, when one spends thousands of dollars on equipment, it’s supposed to be in order to have better quality, not less as compared to what you already have.

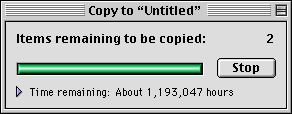

A surprising progress message seen in Mac OS 9 in the late 1990s: At this rate it would take 136.2 years to copy those two files!

People sometimes considered me a resolution/definition snob when I explained why I didn’t want a digital camera from 2004–2008. As it happens, 35-mm film is no great shakes to start with, until 1996 I had a Hasselblad, a 2¼ inch square (6x6 cm) camera that took pictures so sharp that 8x10 inch (20x30 cm) prints were disappointing, I generally wanted to print the Hasselblad’s pictures bigger to see all the detail.

Until the end of 2008, my way of doing digital photography was a “best of both worlds” hybrid, using traditional film cameras and scanning my negatives with the Nikon film scanner, the first of which I bought in 2001. I’ll always keep such a scanner as it gives me access to my archives of negatives and slides I have taken over the decades.

Helpful Links:

- Luminous Landscape: tutorials, discussions and articles on photography, digital and otherwise.

- Négatif Plus: a fantastic professional color lab in Paris that does traditional and digital work equally well.

- Météo France: weather predictions from the official source.

- Freestyle Sales: great deals on photo equipment and consumables.

- Photo Zone: reviews on photo equipment, lenses for the most part.

- LensTip: Another web site with reviews on lenses, though their articles aren’t as succinct as on Photo Zone.

- Digital Photography Review: articles about cameras and lenses as they are released.

- Popular Photography, the web site of the widely distributed magazine in the United States.

- Nikon Rumors: Forecasts and predictions on the products they’ll bring out next.

I’ve been teaching photography almost every day since January 2006, which allowed me to get to know digital cameras very well, the Canon EOS 350 and the Nikon D70 at first, then the 400d and the D80 and D200, etc. People would send me pictures I’d taken with their cameras and I was rarely impressed. Pictures taken with Nikon reflexes, seemed sharp enough, but my scanner still gave twice as much resolution, while Canon digital reflexes made images where the pixels quite frankly had a “children’s finger painting” look.

In 2007, 10-megapixel cameras became common and affordable: the Canon EOS 400, the Nikon D80, D200, etc. I sold my film scanner in April 2007, the same day I bought its successor, the Coolscan V which gives 20 megapixel scans.

100% digital photography; with a digital camera

In the spring of 2008 I noticed that 10-megapixel cameras were indeed capable of giving as much or more definition than a scan of a negative at 20 megapixels. I started wanting to buy one but was interested in an “extra boost” in technology and features before investing. That came along when “Live View” and better performance at high sensitivities became common.

A picture taken with my Nikon F4 and a Nikkor 35–135 mm lens with ISO 160 Kodak Portra film of a brick façade opposite my apartment, scanned at 20 megapixels with my Nikon Coolscan V film scanner.

The same façade taken with my Nikon D90 and the same lens, at ƒ10, a 1/50th of a second and 78 mm, the picture taken with film must have been at 52 mm. The image appears a bit sharper at 12 megapixels and we don’t miss the film grain. Place your mouse cursor over these images to see the difference between film and digital photography.

I bought a Nikon D90 in December 2008 and felt like a Scientologist who had just had his appendix taken out. Naturally I did a film/digital comparison shortly after, taking exactly the same picture of a brick building façade with the same zoom lens, first with my Nikon F4 on ISO 160 Kodak Portra film (said to have the finest film grain of all time), then another zoomed back to get the same coverage on the D90’s smaller digital sensor. Not so surprisingly, the digital image is noticeably sharper than the negative I scanned at 4,000 dpi.

In December 2012 I bought a Nikon D600 after jealously watching advances in technology for four years. A new version of your camera will indeed be better, but not that much better: It’s better to skip generations. The D600 presents all kinds of advantages as compared to my previous camera: Naturally it has twice the resolution at 24 megapixels; image quality is surprising good at very high sensitivities, ISO 3200 looks better than ISO 1600 on the D90; it’s only a little bit bigger and heavier than the D90 (unlike the D800), which is important to me because I take many pictures and portraits with the flash off-camera; and above all, it has a full frame sensor! Rediscovering the 50 mm fixed focal length lens I bought in 1998 was a pleasure because it frames like it always did with my film cameras and my 12–24 mm zoom is that much wider. Over the four preceding years I had bought just one DX lens (usable with the APS-C sensor only) and that one I purchased only because it was on sale new at a ridiculously low price, new.

The end of an era

In 2019 my D600 started to show serious signs of wear in that the rubber padding pealed off, the battery trap wouldn’t close, I had to keep the battery in with packing tape and the flaps on the left side covering the USB & HDMI ports wouldn’t close. None of this bothered me much though by 2021 the ISO button and central pad button fell off, making it difficult to set sensitivity, zoom in to examine pictures in playback mode and do certain settings.

In a camera shop explained these problems, the man said “So it’s coming to the end of its rope” and I said “Oh no, it still takes very sharp pictures and that’s the most important” and he smiled. I asked how much it would cost to overhaul my camera and without going in to details or numbers he advised against the repairs, saying “You could have the camera repaired and the next day the shutter might break down”; he then looked at the shutter count. Although it was about 55,000 out of the 150,000 expected lifespan his line of reasoning convinced me.

At the end of May 2023 my camera stopped working, it displayed “Err” (error) in the top LCD screen, I’d press the shutter button (which cleared out the problem previously), I’d hear the shutter “take” three pictures, Err was still displayed on the LCD screen and the camera simply wouldn’t give up. In that same store I was told the problem was in the mirror cage, parts weren’t available and if I went to Nikon to have it fixed it would be expensive. I didn’t know what “expensive” might mean though if it were much more than 300 euros the repair wouldn’t be worth it. On leboncoin.fr, a classified ads site, found a Nikon D800 for 300€ that does 50% more resolution and is more professional in plenty of ways. I met with Aurélie Noury who sold me the camera which is very clean on the outside and I had the feeling of being reborn after spending a week with my old D90

What is digital photography? What isn’t?

It used to irk me when people are so sure that digital photography means a digital camera. For me, the transition was gradual, from black and white with a flatbed scanner, to color with a film scanner, to the 100% digital process with a digital camera. Someone asked me one day, “How and why was Photoshop used before digital cameras came out?”. I said, “Oh, there are scanners…” and a bored and uninterested look passed across his face. In 2002 and 2003, people would write asking if I had a digital camera, I’d write back saying, “No, I just know Photoshop pretty well.” A year or two later I imagine they just assumed I had a digital camera. To this day, at least 70% of the pictures on my web site are ones I took with film.

What is a digital camera?

A digital camera is one in which the manufacturer has placed a scanner behind the lens, except that we usually refer to it as a sensor. Taking pictures with a digital camera is thus quite a bit like taking pictures with a scanner; many of the adjustments in a camera’s menus typically have their equivalents in scanning software: contrast, white balance, saturation, sharpening, gain (sensitivity), etc. Thus there was no mystery for me the first time I saw a digital camera in 2002, after all not much has changed in photography, ƒ8 will always be ƒ8, a 500th of a second will always be a 500th of a second and ASA 100 is still ISO 100.

Until the end of 2008, my scanner was on my desktop, not inside the camera. For the better because I can make 16x20 inch (40x60 cm) prints without upsampling, with detail in the brightest of highlights and darkest of shadows without taking several pictures and resorting to “HDR”.

The 20 megapixels that my film scanner does can be considered “oversampling” and my 12-megapixel Nikon captures more detail than a 20 megapixel scan of a 35-mm negative. So my D90 makes sharper pictures than my F4 with Kodak Portra and the same lens, that’s nice, it’s just that before I bought my D600, when I had a commission to take pictures for exceedingly huge prints, I’d be more likely to take the pictures with a film camera:

Take a look at a panorama of the Grand Foyer in the Paris Garnier Opera House, printed at 37x120 feet to see an example of a photo project I’d I wouldn’t have done before acquiring a 24-megapixel camera.

Three passengers dozing on a jet plane over the Atlantic Ocean early in the morning. This is the kind of picture that would basically be impossible to take with a typical digital reflex camera.

What about telephones?

Today’s smartphones certainly take pictures of better quality as compared to those made in 2007, though I’m still not impressed. In the typical look of a smartphone photo everything is in focus (their tiny sensors give lots of depth of field), but nothing is particularly sharp. The most recent pocket cameras take pictures wildly sharp, far better than cell phones and rivaling perhaps the best DSLRs and aren’t that much thicker or heavier than smartphones.

That said, I don’t feel like being a complete resolution/sharpness snob and I happily admit that there are times, places and contexts in which taking pictures with a telephone makes perfect sense. There are times when “the medium is the message” as Marshall McLuhan said and the smartphone photo look perfectly fits the subject matter. A great example of this is candid photography, here is a picture I took with my iPod Touch of a young woman sleeping in her seat right next to me on a flight from Reykjavik to Paris in November 2017, above:

How is digital photography different as compared to taking pictures with film?

There are five great differences between film and digital photography:

- You can raise the sensitivity on the fly. To raise the sensitivity with a film camera you have to change the film and stay at that higher sensitivity for the next 35 frames so I never did that, I took all my pictures at ISO 160 before I got a digital camera. Noise in digital pictures is much less noticeable as compared to film grain at the same sensitivity and it’s for certain I take far more pictures between ISO 1,600 and 3,200 than before. Take a look at an example of how being able to raise and lower sensitivity can help. On the other hand, raising the sensitivity brings with it the same compromise in image quality that has always existed since the 1930s.

- You can set the white balance. To correct for artificial light with color film a tungsten filter is necessary. There are filters that give better rendition in cloudy weather and full open shade, but this is such a finicky, fussy concern that hardly anyone uses these filters. Even better are cameras with manual white balance, where you can set Kelvin temperatures between 2,500 and 10,000 degrees, which allows so much more precision and flexibility as compared to automatic white balance.

- It isn’t a good idea to optimize the depth of field. If you want more depth of field while taking pictures with film it’s no problem stopping down to ƒ22 or ƒ32. Everyone says that the digital sensor is more sensitive to the effects of diffraction, meaning that pictures will be less sharp if you stop your lens down more than halfway. And it’s true, after buying my D90 I tried some pictures at ƒ32 and they’re not particularly sharp. Which means that there’s little margin of maneuver as concerns apertures on a digital camera. Thus using Aperture Priority exposure mode is now all the more important; I use ƒ8 or ƒ11, I set it and forget it.

- You can look at the picture right away. This actually isn’t much of an advantage for me, I stare at the image in viewfinder so carefully that I don’t need to look at the picture right away and never crop afterwards. I so often see people looking immediately at the screen on their camera after taking a picture, as if they’re going to see something there they didn’t see in the viewfinder, a practice known as “chimping”: CHeck IMage Preview. Until 2007 cameras mostly had a screen on the back about the size of a postage stamp, which was so frustrating that I said to myself, “That’s okay, I’ll look at the picture in a week at the photo lab at 4x6 inches.” There were times when I would see my pictures twenty minutes after taking them because I’d develop the film right away. That said, seeing the picture right away is after all a great advantage when taking pictures with the flash, allowing me to get just the right orientation on the flash and the right balance between flash exposure and ambient light exposure.

- You can sharpen your pictures. In fact, this is the biggest advantage digital photography has over film, aside from being able to raise and lower sensitivity. If a picture is pretty sharp to begin with, it can be sharpened so much more, such that a brand-new print on glossy paper will have so much depth that it looks 3D. Sharpening doesn’t serve much purpose in scans of negatives, slides or prints because it will just bring out the film grain. Never the less, sharpening can improve a digital image only if the picture is moderately sharp to begin with and only if the sensitivity has not been raised too high, otherwise a sharpening filter will bring out noise that wouldn’t otherwise be so noticeable.

Aside from these five points, there isn’t much difference between film and digital photography.

Why Nikons are better than Canons:

- You see the shutter speed change while adjusting the sensitivity in Aperture priority mode on a Nikon; on a Canon the shutter speed disappears when you adjust sensitivity which is ridiculous, about the only reason to change sensitivity is to get a faster or slower shutter speed (or open or close the lens if you happen to like shutter speed priority). A Canon shows the shutter speed changing when you open and close the lens (as it should) so why not display the shutter speed as the sensitivity is raised or lowered also?

- You can memorize the exposure in spot metering mode by holding down the shutter button halfway. This doesn’t work on a Canon, on their cameras you have to manically press the star button, photo by photo.

- You can zoom in a picture right after having taken it. On a Canon you have to exit playback mode, then go back in order to look closely at a picture.

- Nikons can show pictures in calendar display, you zoom back, back, back and finally you see the pictures displayed by month. Canons allow you to zoom back only until you see two dozen photos on the screen, which isn’t nearly as helpful.

- The use of front and back dials on Nikons is far more ergonomic: the back dial does the “major setting” while the front dial does the “subtle” setting concerning whatever button you’re pressing. Thus, Back dial: ISO, front dial: Auto ISO on or off, Back dial: flash mode, front dial: flash power compensation, Back dial: Autofocus mode, front dial: number of Autofocus points, Back dial: White balance mode, front dial: white balance cold/warm trim, Back dial: Bracketing mode/direction/number of frames, front dial: bracketing exposure spread.†

- Nikon has offered off-camera wireless flash since 2003, while Canon procrastinated until 2011 to offer that and the options for fine-tuning the internal and external flash settings remain far more advanced and evolved on a Nikon.†

Surely there must be ways in which Canons are better than Nikons…

Indeed, there are:- Canons have exposure safety shift: If you head out at noon with the camera mistakenly set to ISO 3200 and ƒ2.8, the camera will stop down (to ƒ8 for example), thus avoiding an overexposed photo when this feature is enabled.†

- Canons have exposure simulation in Live View, as do most other brands so I have no idea why Nikons don’t.

- Autofocus on Canons in Live View is far better since 2011 and I imagine that means autofocus is similarly much better when shooting video. Live view autofocus is incredibly slow on a Nikon, when it works it works fine though it requires lots of patience. I often compose a picture in live view, then leave live view to take the picture since live view autofocus is so slow on a Nikon and autofocus in video is utterly forgettable with a Nikon.

†This option/feature concerns Nikon or Canon’s mid-range and high-end reflexes only.

Most of this page concerns Nikon equipment, what about the other brands?

I bought my second SLR in 1982 the moment I could afford $200 for a Nikon FM and I purchased two lenses in the four following years. These are the kind of choices that dictates one’s purchasing decisions for years and decades thereafter. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s I ignored the other manufacturers because after all, in film photography, the most important component is the lens; film is film no matter what camera you put it in and Nikon makes great lenses.

| I AM | A NIKON MAN |

Before 2007 I was truly unimpressed with Canon’s digital cameras. The EOS 5d was a fantastic camera in its first version, on the other hand their cameras before the EOS 450d (Rebel XSi) and 50d were honestly disappointing, with a muddy image rendition and rarely taking sharp pictures. Canon has solved these problems with image quality with their EOS 500d (Rebel T1i), 60d and subsequent cameras and above all, the EOS 5d Mark II and Mark III.

While image quality is no longer the deciding factor, there remains the question of user interface and there, Nikon has them all beat by a mile. I could easily rattle off almost a dozen examples of how Nikon cameras are easier to use and behave more like a photographer’s creative instrument, instead of how some engineer thinks the ergonomics of a camera should be designed.

Pentax cameras display their images with a truly weird, twisted, over-saturated rendition of color. Perhaps the pictures are not actually like that, though even if this was true, I’d never choose or recommend a camera that doesn’t display its pictures accurately.

Sony has made some fantastic technological advances since they bought Minolta’s photographic division at the end of 2005 and after all, they make most of the sensors in today’s cameras. Their latest reflexes are extremely impressive though buying one would mean replacing all my lenses and flashes.

As for the other brands, Olympus, Fujifilm, Lumix, Samsung, etc… it has to be said all of them are fine cameras and any entry-level reflex is perfectly capable of taking pictures of professional quality today. All of Nikon’s cameras do 24 and 36 megapixels except for the D5 and Df and there aren’t many SLRs with resolution of less than 18 megapixels any more. Quality is no longer an issue, the deciding factor now is the user interface, how much you like the camera.

Here’s a portrait I took with a Minolta DiMage Xt, a 3.2 megapixel pocket camera made in 2003. It looks fine on a computer screen though there’s no point in printing such a photo larger than 5x7 inches.

Does the technical quality of a camera matter?

Actually, not as much as that. Allow me to tell a joke: A photographer is invited to a dinner party by a Manhattan socialite. On arriving he shows the hostess some of his pictures. She is highly impressed, lavishes all kinds of compliments on him and says, “You must have a very good camera!” He’s a bit embarrassed and doesn’t know what to say. All the guests at the soirée then sit down for a glorious gourmet dinner that everyone agrees is majestic. The photographer also agrees and says, “Indeed, that was a magnificent tour de force of fine cuisine. You must have a very good oven!”

As it happens, a moment like this actually happened for me, at a café one evening extravagantly dressed Taki Watanga was singing and dancing and people were taking plenty of “whatever” pictures with their smartphones. I took a few photos that came out well thanks to my innate sense of timing, composition and foresight on which settings to use. I showed one of the pictures to someone and she said “Wow, that’s a good camera!”. I said “It is a camera”. I can yell in to that thing as loud as I want and no one will ever hear me beyond a radius of 15 feet.

Good quality cameras and lenses have always been expensive and before the 1990s I was always chronically underfunded. I remember the Diana camera in the mid-1970s and being thoroughly unimpressed with the vignetting, chromatic aberration, distortion and lack of sharpness of its horrible plastic lens, light leaks on the film because of its cheap plastic body, because I already had a Kodak X15 Instamatic that took better pictures. All I wanted back then was a reflex, if not a Nikon SLR. Thus the current trendy popularity of cameras like the Lomo, Holga and other toy cameras, or even software and “apps” that replicate their image quality/rendition does nothing for me.

Are digital cameras better than film cameras?

Digital cameras have surpassed film with regard to definition, however that extra resolution takes on a camcorder/portable phone look when enlarged beyond 24x36 inches (60x90 cm), unless the camera takes pictures at 24 megapixels or more:

A friend of mine showed me a test print at 185 cm (72 inches) wide of a picture he took with his 12-megapixel Nikon D3. The photo includes a Ferris wheel and the digital image, upsampled that much, describes the Ferris wheel circle as jaggy stair steps, something film grain would never do, whether printed with an enlarger, or scanned at 4,000 dpi and upsampled like all get out. Film grain would never be seen rendered as pixelized jaggy stair steps in a huge enlargement.

Digital cameras don’t seem to offer the exposure latitude that color negative film provides, one has the impression there’s less of a chance of getting detail back in windows in pictures of interiors, in the flames in photos of fire eaters, until you master the Raw file format well. Another thing that bugs me about digital photography is highlights in nighttime photos; there’s a harsh drop-off transition from the light/medium grey to pure white in the street lights and other light sources, sometimes there’s even a darker edge around the pure white.

That said, I’ve been quite happy with my digital reflexes since the beginning of 2009 and my D90 certainly tided me over until Nikon came out with a 24-megapixel camera of reasonable size, weight and price. What’s for certain is we no longer say “digital photography”, it’s just called “photography” and within ten years we’ll be taking pictures at 64 who knows, 128 megapixels in true 32-bit color!

—David Henry